About the Cathedral Chapter in Metz

Obviously, we’re not talking about the kind of chapter you find in a book. A cathedral chapter is something entirely different. Members of a cathedral chapter, or canons, under the pre-Revolutionary regime in France had duties and responsibilities apart from priests. They had benefits apart from priests, too. Read on to see why this became a point of contention.

The Context

Things were not going so well for France in the 1780s. They’d recently been defeated in the Seven Years War against Britain and sent considerable support to the American upstarts who had successfully carried off a revolution of their own. This meant serious debt, and the king, Louis XI, needed to do something about it. So, he convened the Estates General on May 05, 1789, which at the time served as a consulting body more than a decision making one.

Pre-Revolutionary France was roughly divided into three groups: the First Estate, or the clergy; the Second Estate, or the nobility; and the Third Estate, or commoners. Representatives from each of these estates made up the Estates General. Initially, each group had equal membership and votes were counted individually, but that didn’t mean equality. This was especially true when it came to taxes, and the king really had no other choice than to raise taxes in order to pay off the debt.

Here’s the problem. The clergy and nobility were largely exempt from taxes. This meant that between these two groups, they had more than enough power to outvote commoners, so commoners got stuck with the tax burden. When Louis XI convened the Estates General, he Third Estate, sensing they were about to get railroaded, made their discontent known. To appease them, they were allowed to enlarge to the point that their membership was more numerous than that of the other two estates, but this fell apart when it was determined that each estate would now vote as a bloc. If the First and Second Estates voted together, they could still outvote the Third.

Unease had already been building in France, and this was just fuel to the fire. By late May, the Third Estate was meeting on its own. A few members of the other groups filtered over to the Third Estate meetings, and by mid June, the new body had named itself the National Assembly. The king tried to resolve this thorny issue by making a speech and dispersing the Estates General, but the new National Assembly members held firm. The king soon relented, and by July of 1789, the National Assembly had renamed itself the National Constituent Assembly.

It’s worth noting the speed at which such fundamental political and social changes took place, something almost inconceivable to most of us. And the changes would continue.

Liberalism

Referring to the events of 1789-1801 as the French Revolution gives the impression that it was a single, coherent set of events, a natural progression. As convenient as this is, to understand the drama surrounding our Cathedral Chapter in Metz, we have to observe how French society shifted from absolutism and feudalism toward revolutionary liberalism.

We’re not talking about liberalism as many Americans think of it today. In late 18th Century France, liberalism was a political philosophy, not a party mantra. It was concerned with equality, individual freedoms, and free enterprise. Of course, these ideals are antithetical to a system in which your status in a society ruled by an absolutist monarchy is determined at birth, but for a few years, the new National Constituent Assembly and the king made an attempt to get along as a constitutional monarchy. On the face of it, anyway. But liberalism was ready to flex its muscles.

Unrest continued continued across the French nation even after the storming of the Bastille as formerly repressed populations released their pent up anger. Seeing that the existence of privileged classes continued to be a major source of this discontent, the Assembly simply did away with them. Among the nineteen decrees passed by the Assembly in August of 1789, several impacted the clergy. The opening lines of the pamphlet, which refer to them directly, make this clear.

Article 1 abolished the feudal system in its entirety. Members of society were now equal, so the clergy were no longer a formally privileged group. Moreover, the clergy and the nobility intersected and intermingled in France, so this was doubly impactful on the Metz Cathedral Chapter as we’ll see below.

Article 5 abolished tithes. Eventually, a new system for financing the church through the state would be devised.

Article 8 abolished fees collected for parish priests, etc. once centralized salaries were set.

Article 11 made all citizens eligible for office, including ecclesiastical offices.

Article 12 prohibited the flow of money to certain church authorities or bodies outside of France.

Article 13 did away with many other sources of church revenue. This article also specifically mentions cathedral chapters.

Article 14 restricted the amount members of the clergy could make to 3,000 livres regardless of the number of pensions, benefits, etc. they enjoyed.

Later, on August 26, 1789, the National Constituent Assembly adopted the Declaration of the Rights of Man and Citizen. This document alone is a study in the expression of liberalism as a political philosophy, and one of the Declaration’s most notable aspects is the absence of almost any overt reference to religion excepting Article X, which refers to freedom of expression. For all practical purposes, Catholicism ceased to be the national religion of France after its publication.

Then, to help fill the coffers, the Assembly expropriated a significant amount of property, including all church property, through a decree on November 02, 1789. This property was to be sold and the revenues returned to the state to pay down the debt. As we’ll see, this directly impacted the Cathedral Chapter in Metz. In fact, it appears to have been the breaking point that led to the composition of a pamphlet pleading on behalf of the chapter to which our pamphleteer responded.

More decrees and laws were to follow. As things progressed from liberalism to radicalism, the clergy would be reconstituted as a civil force and then suffer massacres and nearly total suppression, although it seems the pamphlet was written before these events took place. However, it is again worth noting the speed at which these changes occurred. Within the space of four months, French politics and society had been restructured and rebuilt.

The Chapter

At the risk of over simplifying things, you can think of cathedral chapters as an evolution of monastic orders. In fact, some cathedral chapters were still associated with orders, and members were required to take vows. Other cathedral chapters had become secularized. They had dissociated from monastic orders, and members might not be required to take vows, although they were still referred to as canons. Chapters often had administrative duties associated with running q cathedral or advising the local bishop, but their major responsibility was in song and music. The Divine Office was often sung, and the chapter had a huge hand in it. In fact, canons had special seating at the time - and still do today - in designated choir stalls. In the pamphlet, we read that one of the major criticisms of the canons of the Metz Cathedral Chapter was they they were not fulfilling these duties.

As cathedral chapters grew and developed, a salary or pension was provided for each member. This was called a prebend, and canons of a cathedral chapter are sometimes called prebendaries as a result. Cathedral chapters also benefitted from donations of money, land, etc. to fund the prebends. This, of course, was in addition to obligatory tithes. Some chapters also acquired real estate through purchase. At the time, land was the primary generator of wealth, so it was important. And, many chapters became quite wealthy.

Although the clergy was the First Estate, nobility was a coveted status. Gradually, many cathedral chapters started to chase prestige, and some became noble chapters. This required ennobling by the king, duke, or prince, and either all or most of the canons who joined a noble chapter had to produce proof of noble lineage. For those chapters who reserved a few spots for commoners, any non-noble hopefuls usually had to have earned a doctoral degree. Thus, cathedral chapters formed quite the elite group.

Put it all together and you can start to see the attraction of joining a wealthy, secular, noble chapter. You had guaranteed income, and often even more than that. Offices within the chapter frequently came with lands and titles, too. Thus, as concepts of nobility started to comingle with church offices, traditional religious motivations played less and less of a role. Again, this is a critique our pampleteer levies frequently against the local canons, referring multiple times to their homes, carriages, entourages, titles, pectoral crosses, and long, crimped forelocks. They were a far cry from what most people imagine when they consider traditional monastic orders, and our author goes to great pains to draw a very negative contrast between the prideful local canons and the more humble Capuchin monks.

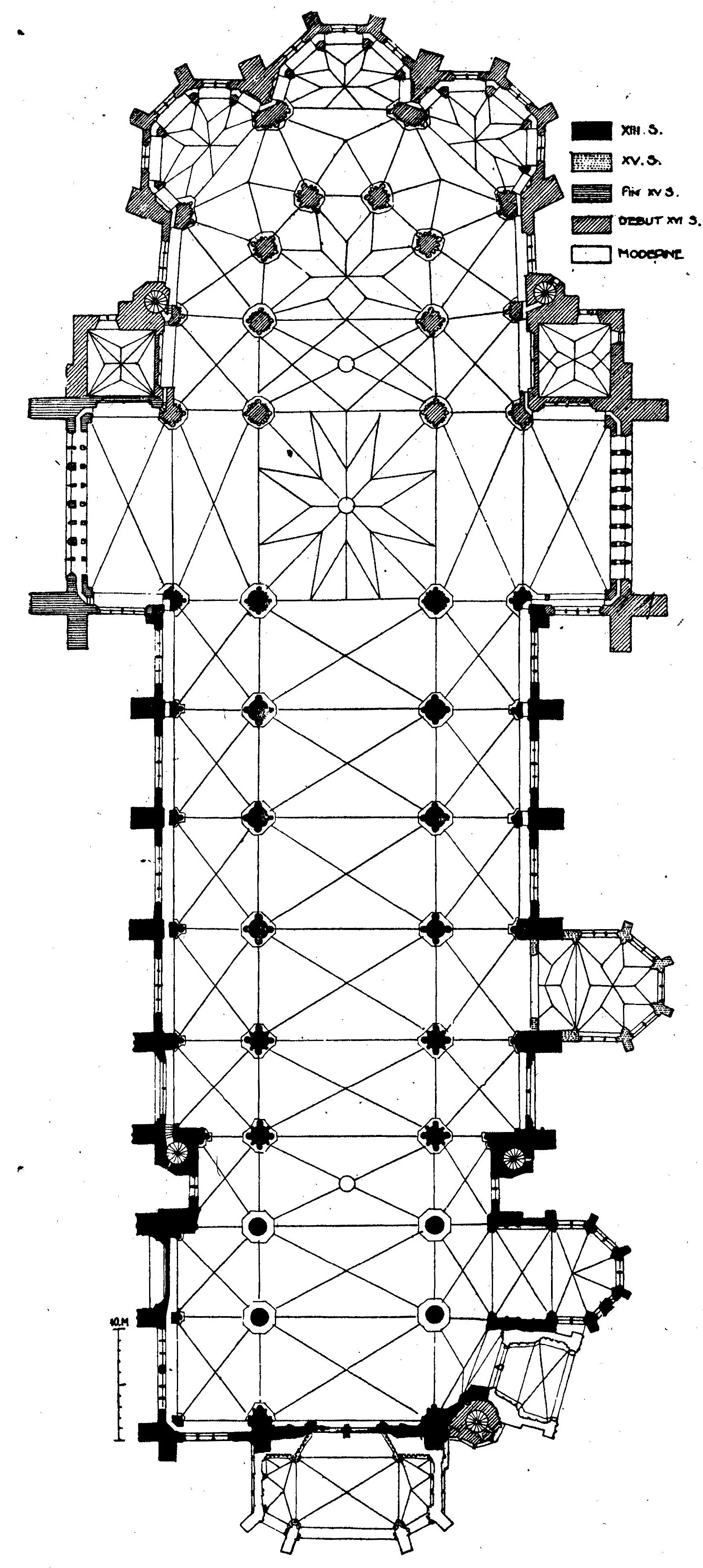

The Chapter of the Cathedral of Saint-Etienne in Metz was ennobled by decree of King Louis XI in 1777. It had 38 canons, 28 of whom had to prove at least three degrees of paternal nobility. The other 10 canonicats were reserved for non-nobles, likely those holding doctorates. However, the timing was bad. Apart from our pamphleteer, we know people were resentful of this move. A complaint about it appears in one of the local cahiers de doléances, which translates as “ledger of complaints.” These lists of grievances were collected by each of the three estates between January and April of 1789.